Our Atradius Exclusive series will provide you with the latest insights from Atradius Economists, annual reviews of corporate payment practices, sector performance and more.

Reports and whitepapers from our industry experts

Latest news and insights

Latest blogs

Helpful guides at your fingertips

Your questions answered

Examples of high quality credit management processes and practices

Success stories from our diverse range of clients

Amid a fragmented global landscape, the EU and India are pursuing different strategies to build economic resilience...

Discover how the global economy is navigating trade tensions and uncertainty, with AI investment driving resilience and shaping growth prospects for 2026 and beyond

Industry growth slows as global trade applies the brakes

Can South Africa's GNU party overcome tensions and structural challenges to unlock GDP growth?

US tariffs, geopolitics and lower demand trigger a contraction of global automotive production in 2026

Tari...

Pharmaceuticals businesses throughout the world are reviewing their operational and...

Viewing 7 out of 207

Europe hopes faster AI adoption will make up for lagging investment in platforms and infrastructure

Atradius Syndicate 1864 will help financial institutions manage trade credit risk more efficiently

This year, Atradius celebrates a remarkable milestone: a century of operations in the Netherlands.

Tariffs and tight margins are...

Thanks to this partnership, our clients in Spain can become sellers on Alibaba.com’s B2B marketplace without paying an entry fee

Europe has committed to a new era in...

Trade tensions, AI investment and geopolitical shifts dominate the global trade agenda. The key takeaway: business must...

Viewing 7 out of 63

Viewing 7 out of 26

Credit insurance is often misunderstood. Myths about cost, complexity, and coverage mean many...

Understanding why credit insurance provides broader coverage, strategic risk management and financial stability compared...

How credit insurers evaluate risk and determine appropriate credit limits

Explore how surety bonds and bank guarantees work, their similarities and differences, and what they mean for...

Explore the trade-offs between credit insurance and self-insurance to protect cash flow and...

Globalisation makes market expansion inevitable, but entering new territories remains a complex and...

Credit...

Viewing 7 out of 33

- What is trade credit insurance?

- What is credit risk?

- Why credit management is important?

- What is business insurance?

- SME Insurance Singapore

- What is debt recovery?

- What is export credit insurance?

- What is political risk insurance?

- How much does credit insurance cost?

- How can I reduce DSO?

- How can I insure my export trade credit?

- How do you know if a business is failing?

- Why do traders take out credit insurance

Every customer is a...

With the backing of Atradius’s resources, EnCom Polymers has been able to expand business with existing customers and go...

BVV GmbH grew internationally and recognised risks such as companies on the brink of insolvency in plenty of time to mitigate the...

Atradius Surety has enabled Vinci Construction France to expand their sources of finance beyond their...

How we are part of Continental Banden Groep B.V.'s business process, minimising risk and supporting sales

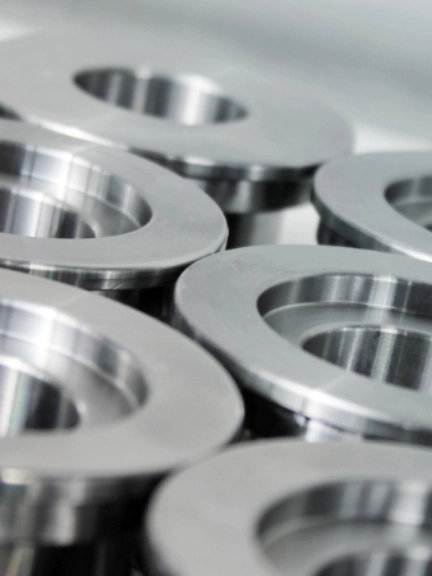

Ben Green, President and Owner at Metalco Incorporated in Chicago, Illinois, explains how Atradius Trade Credit Insurance has helped him...

Viewing 7 out of 8

Omron has achieved sustainable growth while navigating the uncertainties of China-US trade relations and regional manufacturing transformation.

FERM (International) offers competitive payment terms and limits their credit risk to developing countries by using Atradius Dutch State Business (DSB) and...

El Ganso credits our support in helping the fashion brand grow from a domestic-focused Spanish startup to a successful international business.

Calidad Pascual partners with international credit insurance firm Crédito y Caución Atradius to gain additional knowledge of international markets.

By providing open dialogue, insight and valuable credit information we helped Brook Green Supply improve their internal credit...

Janson Bridging (International) uses export credit insurance from Atradius Dutch State Business (DSB) to offer favourable credit terms to customers...

Our agility and local knowledge of worldwide markets and buyers are key reasons why textiles business Georg Jensen Damask say they collaborate...

Viewing 7 out of 9

Case study

Metalco Inc.: Driving new business with quick communication

Ben Green, President and Owner at Metalco Incorporated in Chicago, Illinois, explains how Atradius Trade Credit Insurance has helped him secure new business confidently.

Explore